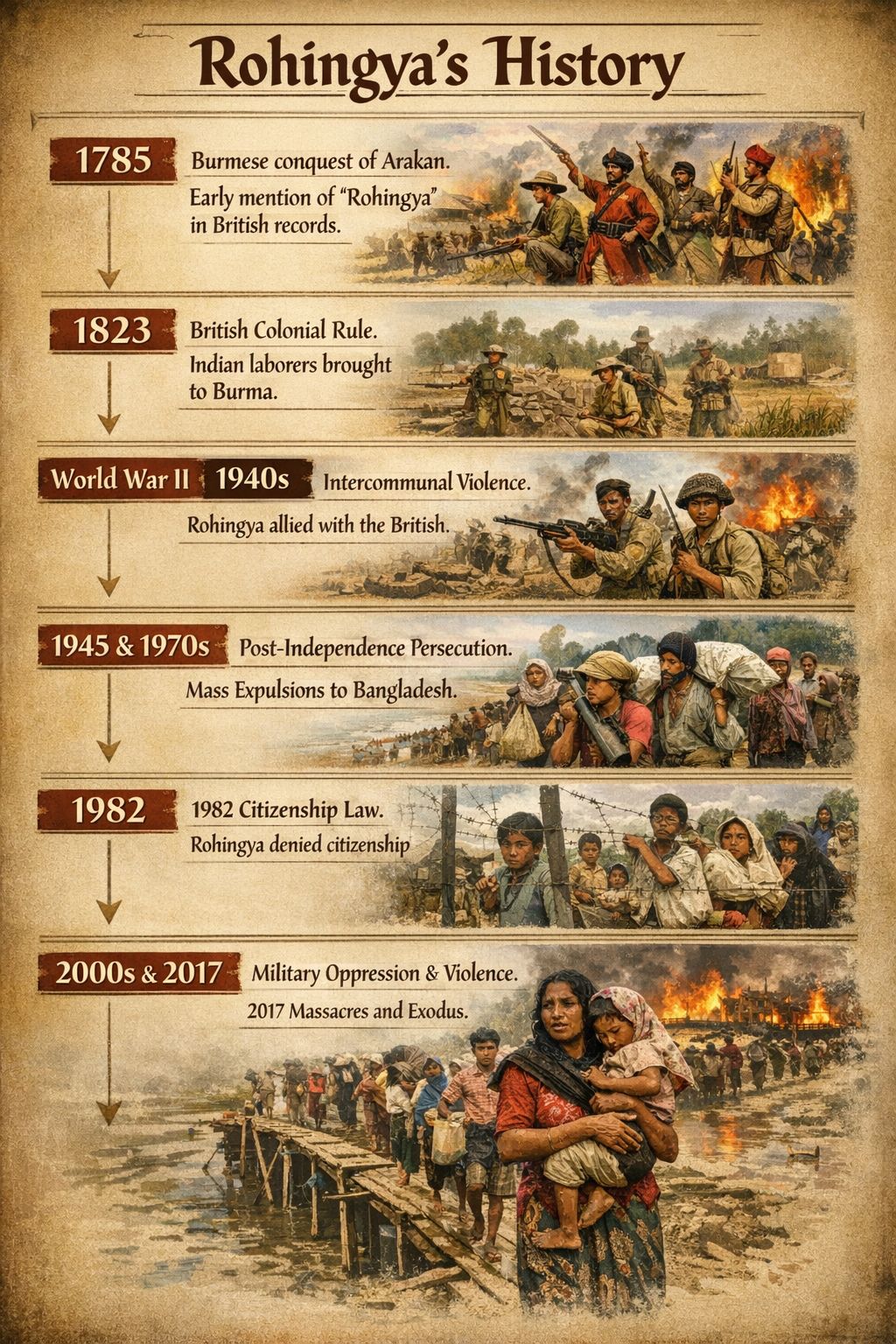

Rohingya’s History

1785 – Burmese Conquest of Arakan

In 1785, the Kingdom of Arakan was conquered by the Bamar, the dominant ethnic group in Burma. The occupation was extremely harsh: thousands of Rakhine men were executed, and many others were forcibly relocated to central Burma. To escape persecution, an estimated 35,000 people fled to British-controlled Bengal by 1799.

Around this period, one of the earliest recorded uses of the term “Rohingya” appeared in British writings. In 1799, British physician and geographer Dr. Francis Buchanan-Hamilton noted that the Muslim inhabitants of Arakan referred to themselves as “Rooinga,” meaning natives of Arakan, while distinguishing them from the Buddhist Rakhines. This record provides early evidence of a distinct, indigenous Muslim population in Arakan known as the Rohingya.

1823 – British Colonial Rule

Following a series of Anglo-Burmese wars, Burma came under British control beginning in 1823. During colonial rule, the British encouraged labor migration from Bengal and other parts of British India to work in agriculture and plantations. These migrants were separate from the Rohingya, who had long maintained their own language and cultural identity.

British governance weakened the traditional authority of Burmese Buddhist kings, whose legitimacy had been closely tied to protecting Buddhism. This, combined with British preference for Muslims in administrative roles, deepened resentment among the Buddhist majority. These tensions contributed to the rise of Burmese Buddhist nationalism and the belief that Burma should belong exclusively to Buddhists—an ideology that later fueled the independence movement.

World War II (1940s)

During World War II, Japan invaded Burma, forcing the British to retreat to India. Burmese nationalists largely supported the Japanese, viewing them as liberators from colonial rule. In contrast, the Rohingya remained loyal to the British due to the protections they had received under colonial administration. This division led to widespread communal violence between Buddhist Rakhines and Muslim Rohingya. The Japanese targeted Rohingya communities for their pro-British stance, while the British armed some Rohingya groups to counter Japanese forces. These actions intensified ethnic conflict and caused significant loss of life and displacement.

1945–1970s – Post-Independence Persecution

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948. The new Burmese government refused to recognize the Rohingya as citizens, despite their historical presence in the region. Some Rohingya groups advocated for joining Pakistan, which further heightened state suspicion.

Under military rule, including leadership associated with General Ne Win, the government launched repeated military campaigns against Rohingya communities. In 1971, during the Bangladeshi Liberation War, large numbers of refugees crossed into Arakan, triggering fear among local Buddhist populations of becoming a minority. In response, the Burmese government forcibly expelled more than 200,000 Muslims—many of them Rohingya—into Bangladesh.

1982 – Citizenship Law

In 1982, Myanmar enacted a new Citizenship Law that formally excluded the Rohingya from the list of 135 recognized ethnic groups. The law granted citizenship only to groups said to have settled in Burma before 1823, the start of British rule.

The government claimed that Rohingya were recent migrants who arrived during the colonial period and were therefore not indigenous. However, historical evidence, including British census records and early literature, demonstrates that Rohingya communities existed in Arakan well before British occupation. This law rendered most Rohingya stateless and stripped them of basic rights.

2000s–2012 – Institutionalized Discrimination and Violence

From the 1980s through the 2000s, Myanmar’s military government promoted a nationalist ideology that merged Burmese identity with Theravada Buddhism. This framework was used to marginalize and persecute ethnic and religious minorities, including the Rohingya, Kokang, and Panthay peoples.

In 2012, large-scale violence erupted between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhist Rakhines in Rakhine State. Evidence suggests that the government facilitated the unrest by transporting armed Rakhine men and providing resources to fuel the violence. Official reports stated that at least 78 people were killed and more than 140,000—mostly Rohingya—were displaced after entire villages were burned. Following the riots, the government imposed curfews, increased military presence, and carried out targeted arrests against Rohingya communities.

2017 – Genocide and Mass Exodus

In August 2017, Myanmar’s military launched what it called “clearance operations” in northern Rakhine State following attacks by a small Rohingya armed group. These operations quickly escalated into widespread atrocities, including mass killings, sexual violence, village burnings, and forced displacement.

More than 700,000 Rohingya were forced to flee to Bangladesh, creating one of the largest refugee crises in the world. The United Nations and multiple human rights organizations later described the actions of the Myanmar military as ethnic cleansing and genocide. To this day, the Rohingya remain stateless, displaced, and denied justice.